THE DISCOVERY OF VIKING WOODSTOWN

In 2003, a team of archaeologists were investigating a field in a townland called Woodstown on the banks of the River Suir, west of Waterford City in advance of the construction of the N25 Waterford City Bypass. During this work, they discovered one of the most important archaeological sites unearthed in recent Irish history. They had found a long forgotten Viking settlement, lost for over a millennia. The discovery was deemed so significant, that the planned motorway was moved in order to preserve the monument.

Unlike Ireland’s other well-known Viking settlements such as Dublin, Waterford, Cork or Limerick, Woodstown never developed into a major town. Instead it was left frozen in time, under the green fields of Waterford until archaeologists rediscovered the site in 2003.

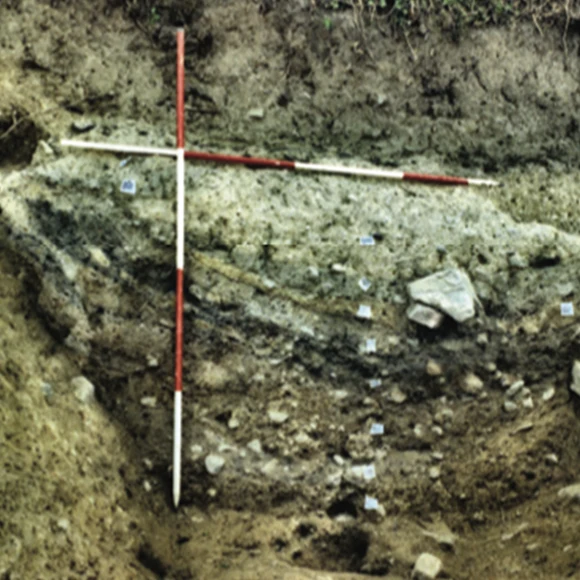

Small scale testing excavations took place at the site in 2003 and 2004 and a supplementary research excavation took place on the site in 2007. Less than 10% of the monument was opened for archaeological excavation, and less than half of this opened area was fully excavated. During the excavations it was found that the uppermost contexts of the occupation levels had been reduced through ploughing, and only features that were cut deeply into the subsoil survived.

Approximately 757 features were recorded – representing pits, structural evidence like post-holes, stake-holes and slot trenches. From this evidence a number of structures were identified including the ground plan of a house. Other features included spreads of redeposited soils and a few hearth sites. Significant areas of craft and industry were also found. The majority of the features were surrounded by a pair of associated D-shaped enclosures.

Despite the challenges posed by centuries of agriculture, it quickly became clear that what did survive at Woodstown was some of the most extensive evidence of Viking activity found in Ireland.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE DISCOVERY

Unlike other Viking settlements in Ireland, such as Dublin, Cork or Waterford, Woodstown never developed into a modern city. That lack of development has left the monument largely intact at foundation level, allowing a unique opportunity to examine a Viking settlement that was ‘fossilised’ in time.

The Enclosures of Viking Woodstown

The largest features discovered on the site were two large parallel ditches that enclosed an area measuring approximately 460 metres long and 150 metres wide. This area contained the vast majority of archaeological features and a large number of artefacts. These large D-shaped enclosures surrounded houses, craft working areas and places of trade.

The Woodstown Warrior

One of the most important features identified in these initial investigations, was the grave of a Viking warrior. Though the acidic soils meant that the remains of the person buried in the grave did not survive, the rich grave goods that they were buried with did. These consisted of a sword, shield, spearhead, axe, knife, hone stone, a ringed-pin and two copper-alloy mounts, one of the most richly furnished Viking graves discovered in Ireland.

“The discovery of Woodstown is a milestone in European Viking archaeology and is arguably the most important individual discovery coming from the Irish construction boom”.

‘The recent discovery of the ninth-century longphort at Woodstown, on the southern bank of the River Suir, near Waterford, has had a profound impact in the international community of Viking scholars”.

From these initial excavations, it became clear that Woodstown was a site of real significance.

The excavations and subsequent investigations and evaluations at Woodstown have revealed a Viking-Age settlement site with a focus of activity dating to c.AD 850–950. The results show that Woodstown wasn’t just a base for raiding and plundering the surrounding countryside. It was a substantial settlement, and a centre for trade, commerce and industry.

You can dig deeper into the results of the initial excavations in the publication Woodstown: A Viking-Age Settlement in Co. Waterford (Russell & Hurley eds, 2014). Available free on the Digital Repository of Ireland.